The fentanyl problem, arms trafficking, migration and the United States’ plan to build a new section of border wall were among the issues Mexican and U.S. officials discussed at high-level security talks in Mexico City on Thursday.

Foreign Affairs Minister Alicia Bárcena and Security Minister Rosa Icela Rodríguez led the Mexican delegation at the 2023 Mexico-U.S. High Level Security Dialogue (HLSD), while Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas and Attorney General Merrick Garland were the top officials in the United States contingent.

The bilateral talks took place amid a surge in migrants to the Mexico-United States border and on the same day the U.S. officially announced its intention to install some 30 kilometers of “additional physical barriers” on its southern border in Texas.

Curtailing the northward flow of fentanyl to the United States, where there were over 100,000 overdose deaths last year, and the southward flow of firearms to Mexico has been a key objective of the two countries for some time.

The challenges Mexico and the United States face were described by officials as “unprecedented and “urgent.”

The fentanyl problem

At a joint press conference at the National Palace following the HLSD, Mexican officials reaffirmed Mexico’s commitment to combating the flow of fentanyl to the United States.

Bárcena said that Mexico was committed to tackling the problem “from all perspectives,” explaining that the government is working to combat the entry of chemical precursors to Mexico, the production of fentanyl and the trafficking and use of the synthetic opioid.

She also noted that Mexico is part of the Global Coalition to Address Synthetic Drugs, which was launched by Blinken in July. Bárcena told reporters that Mexico’s Navy Ministry had proposed the establishment of a group within the coalition to trace the movement of chemical precursors used by criminal groups to manufacture fentanyl and other drugs.

Garland said that the Sinaloa Cartel and Jalisco New Generation Cartel are making fentanyl in Mexico with precursor chemicals from China and then shipping the product to the United States.

“It goes … across our borders and it goes into cartel-related trafficking organizations in the United States. And we are doing everything we can together with our Mexican counterparts to dismantle every stage of that distribution link,” he said.

Rodríguez, repeating a claim that is widely seen as false, said that “Mexico is not a fentanyl producer.”

“It’s a transit country and laboratories dedicated to [fentanyl production] haven’t been detected in the country,” she said.

Later in the press conference, Rodríguez said there was no contradiction in Mexican position and the U.S. position before modifying her earlier statement by saying that Mexico doesn’t produce the chemical precursors used to make fentanyl. Most clandestine drug labs in the country produce methamphetamine, she said.

For her part, Bárcena accepted that there are illegal fentanyl laboratories in Mexico and noted that Mexican authorities have shut down those they have detected.

Blinken said that “U.S. law enforcement has confiscated the equivalent of 279 million potentially fatal doses of fentanyl at our southwest border” over the past year, and noted that “our Mexican partners are also seizing more drugs thanks in part to the collaboration that we have.”

Mexico has seized some 7.7 tonnes of fentanyl since the current government took office in December 2018, according to official data.

Arms trafficking

Blinken said that southbound firearm seizures in the United States have increased more than 65% since last year.

He also said that “Mexican authorities are submitting 40% more firearms trace requests to the United States than they were six years ago, and that enables law enforcement to stop gun trafficking at its source.”

Rodríguez noted that Mexico reiterated its request to the United States to “halt the illicit entry of high-powered firearms” to Mexico, where U.S.-sourced weapons are used in a majority of high-impact crimes such as homicides.

Mexico has previously called for the United States to ramp up inspections of vehicles heading south of the border, and accused U.S. gunmakers of negligent business practices that have led to illegal arms trafficking and deaths in Mexico.

Garland said that “we in the United States well understand the dangers of the military-grade weapons that are being trafficked to Mexico.”

They are a serious danger to the United States and a serious danger to Mexico because they defend the cartels. So we will do everything in our power to stop the unlawful trafficking of weapons to the drug traffickers as part of our fight to break up every link of the chain of the drug traffickers,” he said.

Mayorkas said that the United States would begin sharing with Mexico “a monthly report” on “the intended movement of firearms to the south.”

The aim of the report, he explained, is to “not only to track the progress of our interdiction efforts but also to facilitate in advance our joint operations and investigations.”

Migration

Mayorkas said that the issue of migration was part of the HLSD for the first time on Thursday.

“Our two countries are being challenged by an unprecedented level of migration throughout our hemisphere,” he said.

“The United States is committed to continuing to work closely with Mexico as we implement the model that pairs the historic expansion of safe, orderly, and lawful pathways for migrants to come directly to the United States, or elsewhere to obtain humanitarian relief outside the grip of the smugglers,” the homeland security secretary said.

Mayorkas said that “swift repatriation” and a ban on re-entry were among the consequences for “those who do not use those lawful means to enter our country.”

He noted that the United States on Thursday “announced its agreement with … Venezuela to repatriate Venezuelan nationals who do not take advantage of the lawful pathways and instead arrive irregularly at our southern border and do not qualify for relief.”

“The work we do together would not be possible without the close collaboration we enjoy with our partners in Mexico and with our colleagues throughout the 21 countries across this hemisphere who are party to the Los Angeles Declaration,” Mayorkas said.

Bárcena acknowledged that Mexico and the United States have recently seen “historic” levels of migration, and said that the entire world is currently witnessing “massive human migration.”

She thanked the U.S. government for opening up new legal pathways for migrants before reiterating the Mexican government’s commitment to addressing the migration phenomenon by attending to its root causes, including “inequality, poverty and violence.”

“The migration we’re seeing comes from the south,” Bárcena said, adding that President López Obrador is “very interested” in holding a summit attended by officials from the 11 largest source countries of migrants to the United States via Mexico.

Such a meeting would focus on “development” and other “actions we can take” to address the migration phenomenon, she said.

López Obrador, whose government has supported the rollout of employment programs in Central America, last week urged the U.S. Congress to approve a support plan for countries in the region with economic, social and political problems that are forcing large numbers of people to leave.

“A comprehensive support plan … so that Venezuelans, Cubans, Nicaraguans, Ecuadorians, Guatemalans, Hondurans don’t have the need to emigrate,” he said.

The resumption of border wall construction

Mayorkas said that the Biden administration remains opposed to a border wall, despite its announcement that it had waived 26 federal laws in southern Texas to allow the installation of additional barriers in Starr County, located in the Rio Grande Valley region of the Lone Star state.

“I want to address today’s reporting relating to a border wall and be absolutely clear: There is no new administration policy with respect to the border wall. Allow me to repeat that: There is no new administration policy with respect to the border wall,” he said.

“From day one, this administration has made clear that a border wall is not the answer. That remains our position, and our position has never wavered,” Mayorkas added.

An announcement he published in the U.S. Federal Register on Thursday said there was “an acute and immediate need to construct physical barriers and roads in the vicinity of the border of the United States in order to prevent unlawful entries into the United States.”

But Mayorkas said that “the language in the Federal Register notice is being taken out of context and it does not signify any change in policy whatsoever.”

“The construction project reported today was appropriated, funded during the prior administration, in 2019, and the law requires the government to use these funds for this purpose, which we announced earlier this year – in June, to be precise,” he told reporters in Mexico City.

“We have repeatedly asked Congress to rescind this money, but it has not done so and we are compelled to follow the law.”

Mayorkas said that the Biden administration “believes that effective border security requires a smarter and more comprehensive approach, including state-of-the-art border surveillance technology and modernized ports of entry.”

“We need Congress to give us the funds to implement these proven tools,” he said.

Bárcena said that Mayorkas had effectively “clarified” the United States’ position, and declared that Mexico believes in bridges rather than walls. She said her understanding was that the United States would use the funds appropriated by Congress not to add to the wall but to install technology and build other infrastructure such as roads to aid the detection of migrants.

Mayorkas subsequently remarked: “I am happy to repeat what I said earlier so that there is no lack of clarity. From day one, the policy of this administration has been that there will be no more wall construction. That remains our policy and we have never wavered from it.”

Earlier on Thursday, López Obrador asserted that the United States’ decision to add to the border wall between Mexico and the U.S. was “a backward step” that won’t solve the migration problem.

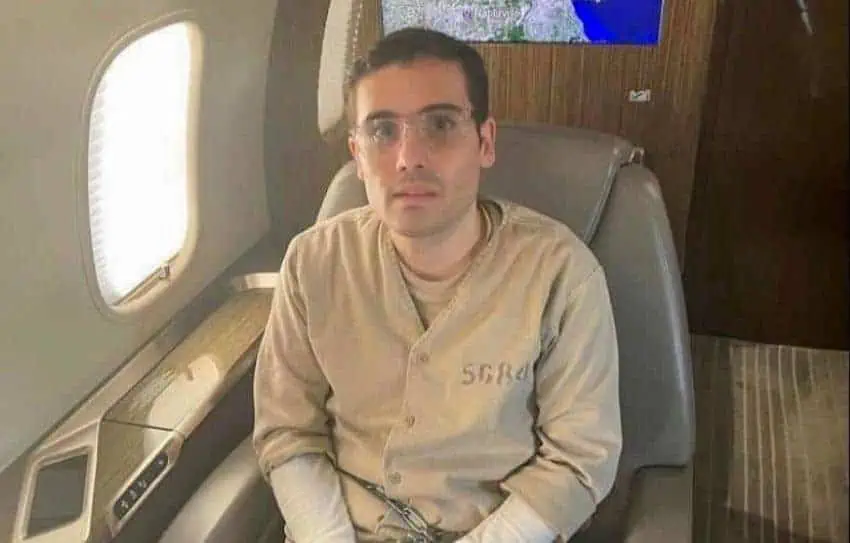

The extradition of Ovidio Guzmán

Garland thanked Mexico for extraditing Ovidio Guzmán López, son of convicted drug trafficker Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera, to the United States, where he faces charges including drug trafficking and money laundering.

“Just three weeks ago, Ovidio Guzmán López, a leader of the Sinaloa Cartel and the son of El Chapo, was extradited from Mexico to the United States. He is one of more than a dozen cartel leaders we have indicted and who have been extradited to the United States,” he said.

“He will not be the last. We are grateful to our Mexican counterparts for that extradition. We recognize that these cartels are terrorizing Mexican communities, and we recognize that this action would not have been possible without the sacrifice of Mexican law enforcement and military service members who gave their lives in pursuit of justice.”

The broader Mexico-U.S. relationship

Blinken said that “more than ever before” in his 30 years of experience in foreign policy, “the United States and Mexico are working together as partners in common purpose.”

He said that “the scale and scope” of the challenges the two countries face is “unprecedented” and the bilateral partnership is as well.

“Two years ago, United States and Mexico launched the Bicentennial Framework for Security, Public Health, and Safe Communities. And in doing this, we acknowledged a shared responsibility, a shared responsibility as neighbors to enhance the safety, the security, the well-being of our people,” Blinken said.

“We agreed to work as equal partners to tackle the challenges like illicit drugs, illegal firearms, human trafficking. And we committed to a comprehensive approach that includes bolstering the rule of law, fighting corruption, improving public health, and investing in broad-based economic opportunity,” he said.

Although the two countries have outstanding disputes on issues including energy and corn, Bárcena said that the state of the relationship between Mexico and the United States is “excellent.”

Mexico News Daily