The story of Australian Roderick James Marston (at times referred to as Martson) – the photographer who became a Zapatista – was largely unknown until the 1990s, 60 years after his death, when his great granddaughter Erin Reid discovered a box of his journals and photos taken during the Mexican Revolution in the basement of his Vancouver home.

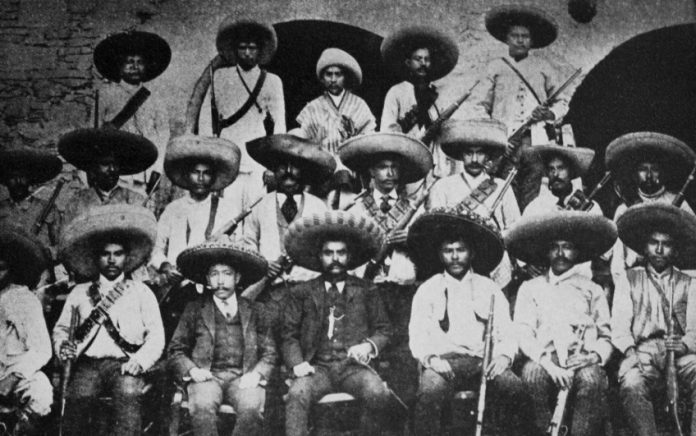

Reid has not yet released the contents to the public but has confirmed that the journals and photographs document his time with the Zapatistas. He has been referenced in Zapata biographies simply as “El Gringo”.

Marston was an intrepid traveler and adventurer. From an early age, he began traveling the world in search of adventure and his wealthy parents indulged his wanderlust. He was also a photographer, inventor, miner, and entrepreneur.

His travels eventually took him to Vancouver, Canada where he caught gold fever. His desire to become a prospector took him south to the United States, settling in San Antonio, Texas and acquiring two mining properties.

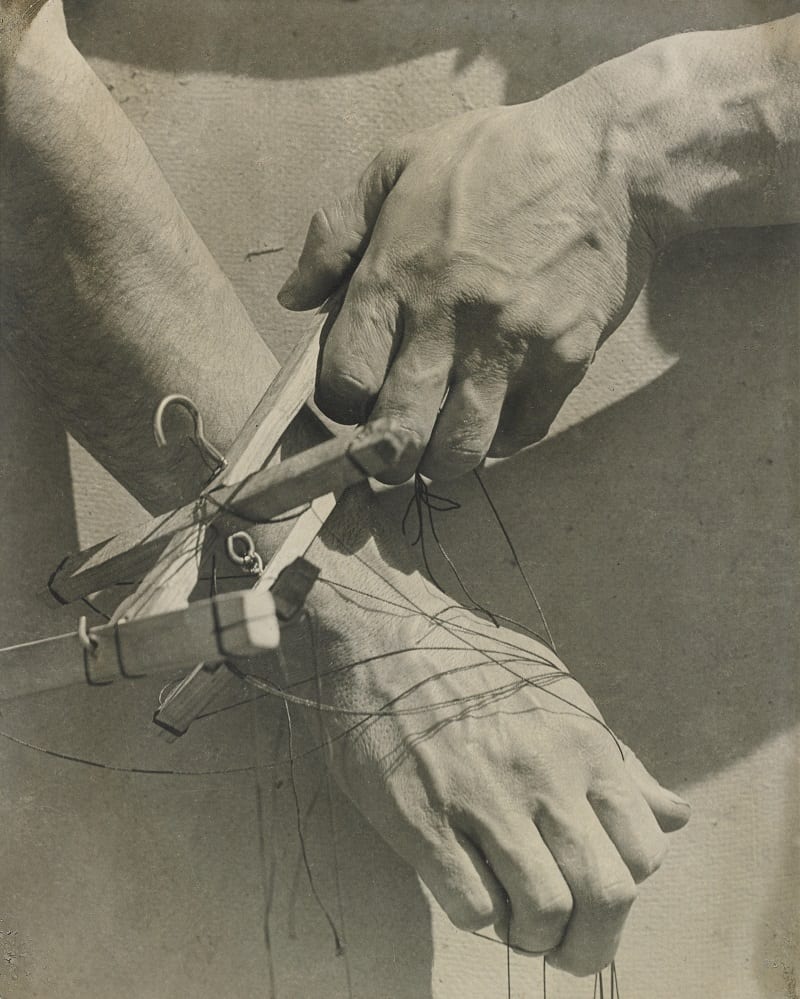

His scientific skill and intuitive sense of timing led him to invent a method of mining using explosive devices he invented to rip away the hard rock revealing the hidden treasure within – veins of gold to be exploited. His expertise gained him huge profits and gave him an edge over the other gambusinos (prospectors).

Eventually gold mines in the region began to dwindle, so Marston, backpack slung over one shoulder, traveled further south into Mexico to seek new adventures.

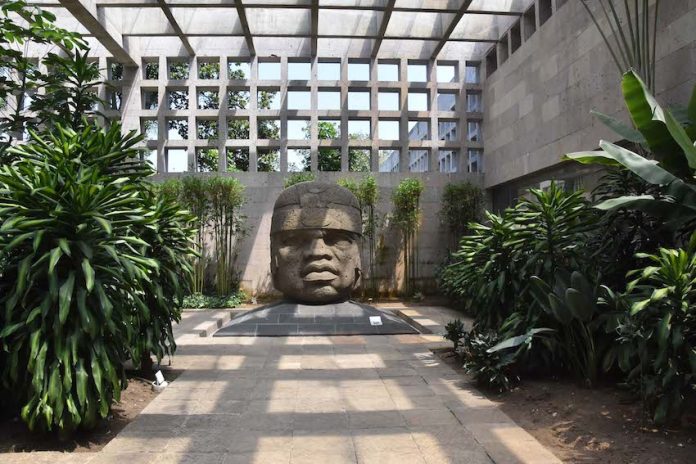

He received permission from President Porfirio Díaz to settle in the city of Tehuacán, Puebla to carry out “scientific work” which for Marston meant mining. He immediately acquired a silver mine and once again employing his unique explosive techniques, began making large profits.

His profits were so immense that he built a large estate and hired twenty people to staff it. For the next six years he spent his time making money, designing new inventions, and indulging in his true passion: photography.

However, the Mexican Revolution of 1910 interrupted this more settled life for Marston.

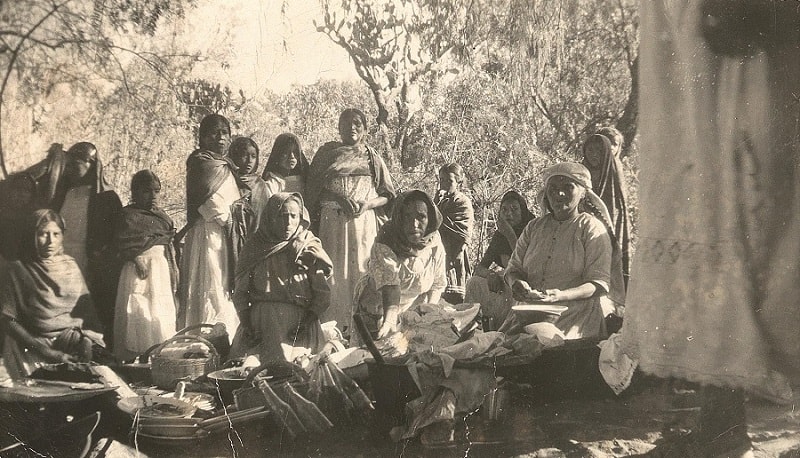

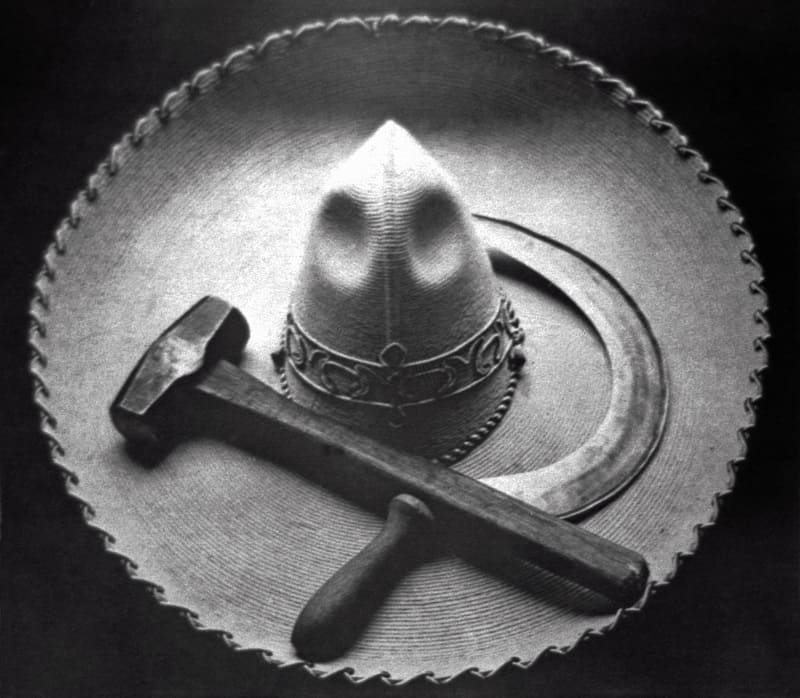

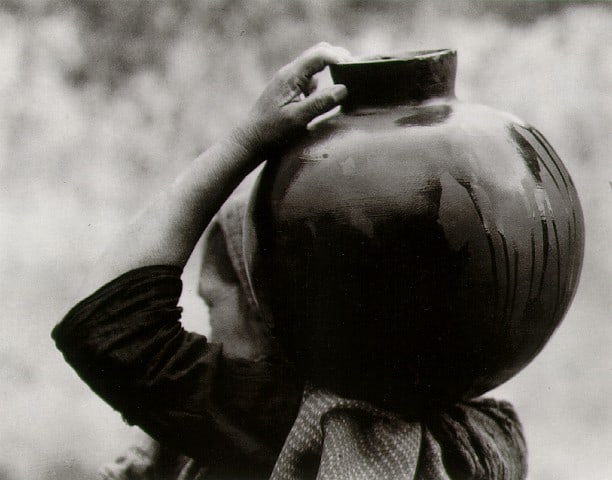

In the leadup to the war, General Emiliano Zapata’s army dominated the states of Morelos and Puebla. The slogan of the Zapatistas was “Land and Freedom”. Their goal was restitution of the land to the peasants – land currently owned by wealthy landowners. As the Zapatistas advanced through the area, ranches and estates fell one by one – the land then distributed to peasants.

According to the limited accounts available, when they reached Marston’s property, he and his employees put up a fierce defense but they were no match for Zapata’s army – the estate was in ruins, most of his servants killed, and Marston taken prisoner.

The Zapatistas considered him a “gringo” (born in the United States) and Zapata ordered him to be executed by firing squad. Marston, in broken Spanish, tried to explain that he was not a gringo. The story goes that by displaying a tattoo of the British flag on one of his arms, he convinced them he wasn’t an American. According to interviews conducted with his great-granddaughter, he had obtained the tattoo while spending time with the British merchant navy during his earlier travels.

The story may be apocryphal, but Zapata decided to spare him if he agreed to fight with the Zapatistas.

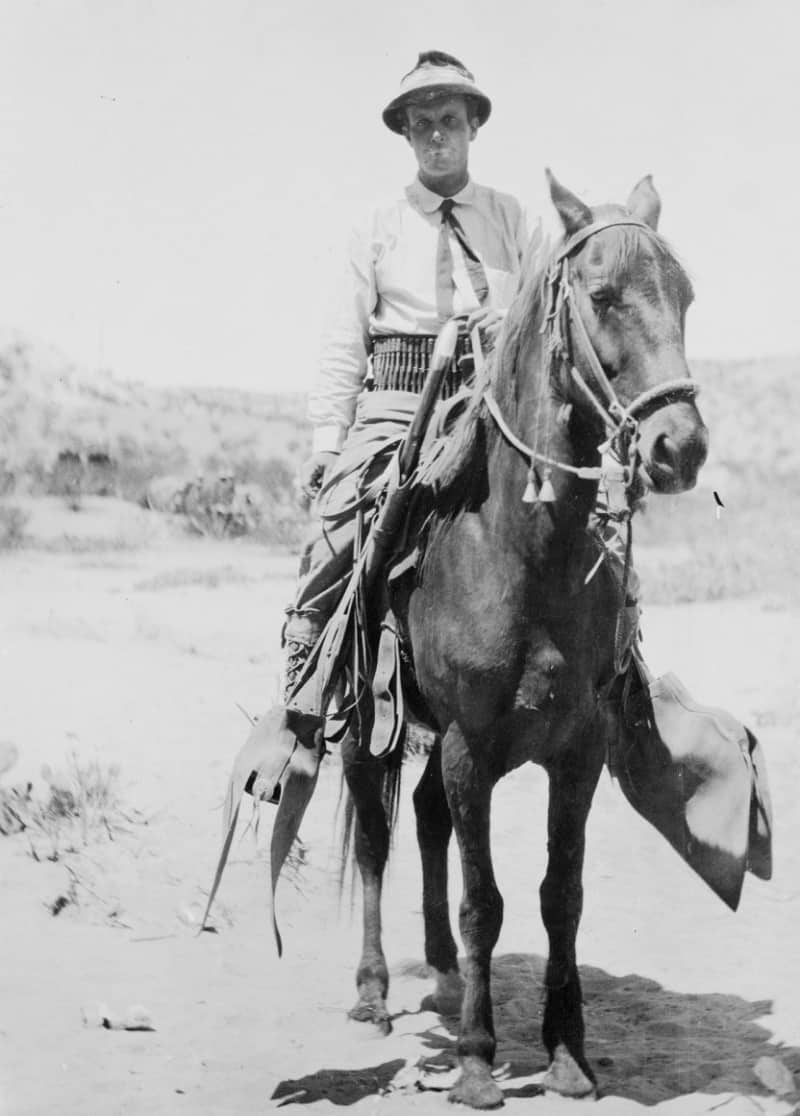

Marston, donning the Zapatista hat and carrying bandoliers on his shoulder, became part of Zapata’s army and was assigned to a battalion in Puebla. Due to his experience with explosives, Zapata put him in charge of blowing up the roads and railways being used by the federal army to fight the Zapatistas.

In 1911, Porfirio Díaz was overthrown and revolutionary leader Francisco I. Madero marched triumphantly into Mexico City to claim the presidency. Zapata – as the revolutionary leader of the south – began peace negotiations with him in the hope of sharing power in the new government. However, it quickly became apparent that Madero was not interested. Considering him a traitor to the cause, Zapata restarted the armed struggle for land – this time fighting the federal forces under President Madero.

On one occasion General Zapata himself ordered Marston to blow up a hospital where wounded federal soldiers lay dying. Marston refused, considering this a criminal act. Zapata saw his disobedience as a betrayal of the cause and ordered him to be executed, for a second time. But the Zapatistas had come to like and respect the gringo – even calling him Captain Marston – and intervened to save his life.

Marston did not blow up the hospital, but he continued to fulfill his revolutionary duties until he was eventually captured by the Madero federal army and imprisoned. Madero, who was at the time seeking the support of foreign nations – and believing Marston to be a British citizen – gave him a reprieve on one condition: exile. Once more, the tattoo had saved his life.

He made one last trip to the Zapatista camp where he had spent so much time to say his goodbyes to his comrades, who were by now his friends, and collected his most valuable possessions – his photographic equipment, his photo negatives, and his journals – and departed for the United States.

His days of wandering, however, were not yet over. He traveled around the United States trying his hand at managing land, factory management, and even at one point selling Dr. W. B. Caldwell’s Syrup Pepsin (an early U.S. patented laxative) until he migrated north to Canada – where he finally settled down in Vancouver to start a family.

It is believed that he died there in 1933, at the age of 59. All that remains are his journals and more than 500 photos of Zapata and the Zapatistas. His days of wanderlust had finally come to an end but many of the details of his adventures in Mexico remain shrouded in mystery.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.