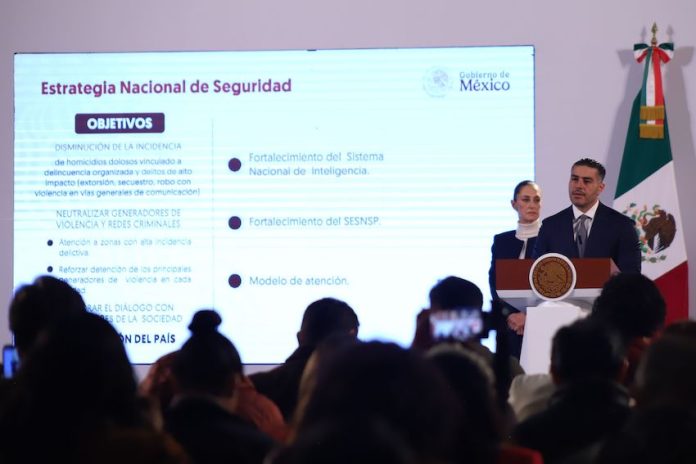

The new federal government on Tuesday presented its national security strategy, based on four key pillars including the consolidation of the National Guard and the strengthening of intelligence gathering.

Security Minister Omar García Harfuch told President Claudia Sheinbaum’s morning press conference that “under the leadership of the president of Mexico, … we’ve designed a national security strategy based on four core tenets.”

The four “ejes” — axes or core tenets — of the strategy designed to reduce crime in a country with major security problems are:

- Attention to the root causes of crime.

- Consolidation of the National Guard.

- Strengthening of intelligence and investigation practices.

- “Absolute” coordination within the federal government’s security cabinet, and with state authorities.

“The first axis is attention to the causes,” said García, who served as security minister in Mexico City between 2019 and 2023 while Sheinbaum was mayor of the capital.

“We will continue with the strategy that began during the government of president Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the strategy of attending to the most vulnerable families as a priority, reducing poverty, closing gaps, [combating] inequality and creating opportunities so that young people have access to a better quality of life,” he said.

“This will allow us to move away from crime and the recruitment [of young people] by crime groups,” García said.

One program launched by the previous federal government that seeks to provide work opportunities for young Mexicans and steer them away from a life of crime is the “Youths Building the Future” apprenticeship scheme.

The provision of social and welfare programs is the central aspect of the first part of the so-called “hugs, not bullets” security strategy pursued by the López Obrador administration.

The second part of the strategy’s nickname is a reference to the desire to avoid violent confrontations with crime groups wherever possible.

García said that “the consolidation of the National Guard, within the National Defense Ministry [Sedena], is extremely important.”

The National Guard, a 133,000-member force created during López Obrador’s six-year term, was placed under the control of Sedena last week after both houses of Congress approved a constitutional bill last month aimed at reestablishing military control of the agency.

While highlighting the importance of strengthening the security force, García acknowledged the precarious security situations that prevail in “some communities in our country” as well as the immense “firepower” of organized crime groups.

“We absolutely need a force like the National Guard to provide support … to hundreds of thousands of families in Mexico,” he said, adding that the security force will also support the country’s investigators and intelligence agents.

Although the National Guard is now under army control, García stressed that it is a “police institution,” albeit one with a “military doctrine” and “military discipline.”

“… There are families that today don’t have access to trustworthy municipal police or state police that are completely equipped [to do their job]. That’s where the National Guard will play an important role,” he said.

García rejected claims that putting the National Guard under the control of the army amounted to increased militarization of public security in Mexico.

“It’s false that there is militarization. What we’re doing is taking advantage of the capacities of the National Defense Ministry,” he said.

With regard to “the third axis — the strengthening of intelligence and investigation — the security minister said that the aim is to not just “react” to crimes but to “anticipate” them as well.

The government will use “intelligence” and “the most advanced technological resources to analyze data, identify [criminal] patterns and understand the dynamics in the areas with the highest incidences [of crime],” García said.

“That’s how we can develop the most effective strategies to combat criminal organizations,” he said.

To increase intelligence capacities, an intelligence and police investigation division will be created within the federal Security Ministry, García said.

The division will be supported by forensic experts including analysts, field researchers and intelligence agents, he said.

Speaking about “the fourth axis” — coordination between authorities — García said that insecurity is a problem that is a “shared responsibility” and which requires a “unified response.”

“That’s why we’re going to have absolute coordination between the institutions of the security cabinet,” he said, referring to the president’s office, the Security Ministry, the Interior Ministry, the army and the navy.

García also said that the federal government will coordinate closely with state authorities “when necessary.”

3 objectives for the construction of ‘lasting peace’

The security minister said that the government has also “established three main objectives for the construction of lasting peace in the country.”

![Speaking of her administration's security strategy, Sheinbaum emphasized "prevention, intelligence and presence [of security forces]."](https://mexiconewsdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/WhatsApp_Image_2024-10-08_at_9.57.09_AM.jpeg)

- The reduction of the crime rate, “particularly homicides and high-impact crimes such as extortion.”

- The neutralization of “generators of violence and criminal networks, with attention to areas of high criminal incidence.”

- The strengthening of “prevention capacities and social proximity of local police.”

To achieve the objectives, “different lines of action” have been developed, García said.

Among them: the strengthening of the national intelligence system and the strengthening of the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System.

García also said there will be a “comprehensive” focus on combating high-impact crimes that starts with law enforcement authorities and is continued by prosecutor’s offices, the country’s courts and the prison system.

In addition, he said that a specific “strategy of intervention” has been developed to combat high-impact crimes in the states of Guanajuato, Baja California, Chihuahua, Guerrero, Jalisco and Sinaloa, all of which have significant security problems.

“From the security cabinet of the government of Mexico, we’re going to work with all the federal entities because we’re convinced that to achieve lasting peace in the country, we must accept that security is a shared responsibility,” García stressed.

“I’ll take the opportunity to give special thanks to the federal attorney general Dr. Alejandro Gertz Manero, for his resolute collaboration … and for providing the operational and investigative capacities of the Attorney General’s Office for the success of this strategy,” he said.

Sheinbaum: the ‘war against narcos’ won’t return

One week after she was sworn in, President Sheinbaum reiterated that her government won’t pursue the kind of militarized “war” against drug cartels that former president Felipe Calderón launched shortly after he took office in December 2006.

“The first thing, which is very important, is that Calderón’s war against narcos won’t return,” said Sheinbaum, who nevertheless will continue to use the military for public security tasks.

Homicide numbers increased significantly during Calderón’s government before continuing to rise during the 2012-18 term of Enrique Peña Nieto. Murders increased even more in the first half of López Obrador’s presidency, before declining somewhat in the second half of his six-year term.

Seeking to further differentiate her government from that of Calderón, Sheinbaum declared that “we’re not looking [to carry out] extrajudicial executions.”

“What are we going to use [to combat crime]? Prevention, intelligence and presence [of security forces],” she said.

The new president has not had a good start to her presidency in terms of security. The Mexican army killed six migrants in Chiapas just hours after she was sworn in, apparently mistaking them for criminals, while the mayor of Chilpancingo was beheaded on Sunday.

A fierce battle between rival factions of the Sinaloa Cartel continues to rage in Culiacán and other parts of Sinaloa, while 12 bodies were found on the streets of Salamanca, Guanajuato, last Thursday.

On Tuesday morning, Sheinbaum acknowledged that Guanajuato is easily the most violent state in Mexico in terms of total homicides.

She said that there is also a serious addiction problem in the state, and told reporters that León “is the city with the highest number of poor people.”

“Guanajuato is a state with an average salary below the minimum. Clearly there is a model of development that failed,” she said of a state that has been governed by the conservative National Action Party (PAN) for more than three decades.

During her mayorship, Sheinbaum managed to reduce homicides and other serious crimes significantly in Mexico City.

She, García, other federal officials — and millions of Mexicans fed up with violence and insecurity — will be hoping that the same kind of success can be replicated on a national scale via the implementation of the security strategy outlined on Tuesday morning.

With reports from Milenio, Reforma and El Universal