This is my tenth week in a row thinking and writing about why Mexico is a key — and strategic — enabler of the United States’ growth and development. When I started, I had little doubt about that conclusion. But as I dug deeper into each topic, the conviction only grew stronger: one of the most underappreciated strategic assets the United States has today is Mexico.

I began this series by looking at the policy framework and priorities shaping the United States today.

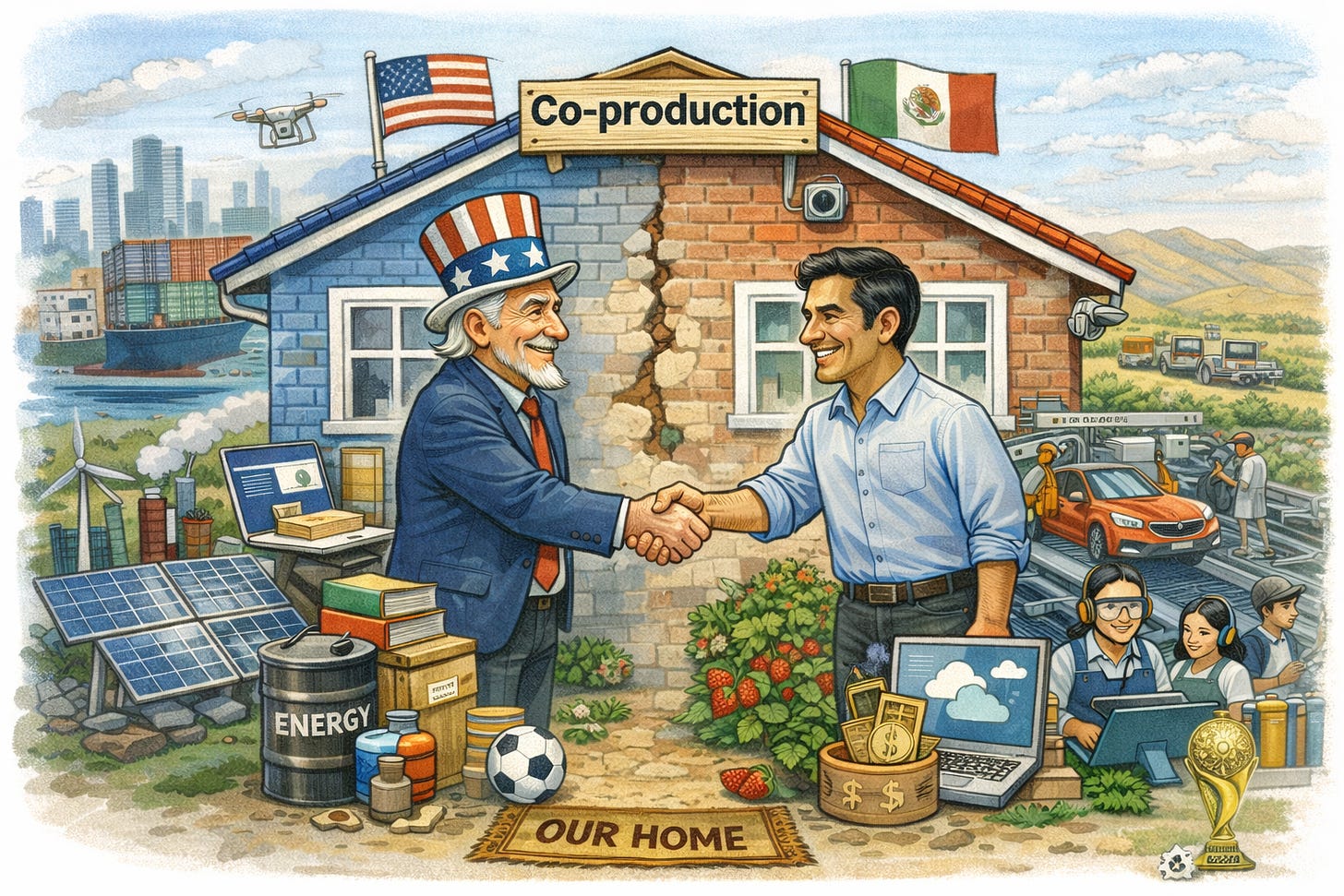

Stripping away the noise, I identified four guardrails: the need to decouple from China, re-industrialize the economy, move from free trade to managed (or “fair”) trade and treat economic policy as national security policy. What became immediately clear is that each of these pillars has a Mexican component that can accelerate — and de-risk — the U.S. path forward.

Take China. The challenge is not simply reducing dependence; it’s doing so without breaking supply chains or slowing growth. Mexico offers the only realistic answer at scale: proximity, integration, trust and capacity. North America competing together is far more effective than the United States competing alone.

Re-industrialization tells a similar story. The U.S. needs factories, workers and speed. Mexico brings a young labor force, decades of manufacturing know-how and seamless integration with U.S. production systems. This isn’t outsourcing — it’s co-producing, and it’s the difference between wishful thinking and execution.

On trade, the U.S.–Mexico relationship shows why not all deficits are created equal. When measured in value added rather than gross flows, what looks like an imbalance turns into interdependence. Mexico is not just selling to the United States; it is buying from it, assembling with it, and exporting jointly to the world. This is managed trade that actually works.

Then there’s national security. Energy, AI, autos, agriculture and digital services all share the same reality: resilience now depends on regional systems. Mexico anchors U.S. energy exports, enables AI hardware and data infrastructure, stabilizes food supply chains, sustains automotive competitiveness, and absorbs a growing share of U.S. services exports. Security today is not isolation — it’s reliable integration.

Across demographics, the logic repeats itself. The U.S. is aging. Mexico is younger. The U.S. needs workers, consumers, and growth. Mexico is becoming a larger, wealthier market next door. Thirteen million people lifted out of poverty in six years is not just a social achievement — it’s a future demand signal for U.S. goods and services.

Energy showed us that Mexico is not a vulnerability for the U.S., but a pressure valve and a growth outlet. Agriculture reminded us that food security is regional, seasonal and climate-dependent. Services trade revealed a quieter truth: the U.S. runs a surplus with Mexico in the sectors that define advanced economies — education, finance, digital, logistics and travel.

And the auto industry made the case most starkly of all. In a world of stagnant demand and aggressive Chinese competition, North America either competes together — or loses separately.

Seen as a whole, the conclusion is hard to ignore. Mexico is not a side story to U.S. growth. It is not a short-term convenience. It is not a problem to be managed. Mexico is a strategic enabler of the United States’ competitiveness, resilience and long-term prosperity.

With all that said, this does not mean Mexico is without serious challenges — far from it. Organized crime is a real and pressing problem. Mexico is also the final stop for millions of migrants fleeing even worse conditions farther south, a geographic reality that can be seen either as a burden or as a strategic asset for the United States.

My take is simple: this is not an issue to outsource or ignore, but one to address in close coordination. There are other challenges too, of course. But that leads us to the only question that really matters: what are we going to do about it?

Mexico is not going anywhere. The United States isn’t either. And whether we like it or not, this partnership is not optional — it’s structural. We are not just neighbors; we are roommates. We live in the same house. And if we’re going to share it, we might as well work together to make it the best house on the block.

Now, a couple of personal closing notes.

Ten weeks ago, I opened this Substack simply to put my thoughts out there instead of keeping them to myself. Back then, quite literally, with zero readers. I’m wrapping up this tenth week with 100 subscribers and more than 2,500 readers. I genuinely want to thank everyone who shared these texts, sent a kind note, left a comment, or simply dropped a like. It means more than you know.

And finally, I’m writing this last piece from a hospital room, looking at my three-day-old child. I think it’s time to pause the writing for a bit and fully enjoy this once-in-a-lifetime, out-of-this-world experience.

But don’t worry… I’ll be back. Viva North America!

Pedro Casas Alatriste is the Executive Vice President and CEO of the American Chamber of Commerce of Mexico (AmCham). Previously, he has been the Director of Research and Public Policy at the US-Mexico Foundation in Washington, D.C. and the Coordinator of International Affairs at the Business Coordinating Council (CCE). He has also served as a consultant to the Inter-American Development Bank.