A Danish fund will invest US $10 billion in a green hydrogen plant in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, President López Obrador said Friday.

Speaking at his morning press conference, López Obrador said that the plant will be located in an industrial park, or “development hub,” near Ixtepec, located inland from the port city of Salina Cruz, Oaxaca.

The government is developing a trade corridor across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec between Salina Cruz on the Pacific side and Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz, on the Gulf of Mexico. It will include a modernized railroad to be used by freight and passenger trains and 10 industrial parks.

López Obrador told reporters that “a Danish company – a financial economic fund from Denmark” will operate the industrial park near Ixtepec, adding that it will invest $10 billion in the project.

“They’re going to produce energy, green hydrogen to substitute fossil fuels. New ships will run on green hydrogen and all this will be produced in the Isthmus,” he said.

“We’re talking about the era of no contamination, of everything being done to avoid climate change. This agreement is about to be signed. I won’t see the finished project [during my presidency], but I will leave all agreements and everything in place. This will help the isthmus a lot.”

López Obrador didn’t name the fund he was referring to, but he said in August that Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners (CIP), a Danish investment firm focused on renewable energy, was going to build a green hydrogen plant near Salina Cruz to supply ships.

Reuters contacted CIP on Friday and a spokesperson said they didn’t know whether López Obrador was speaking about the firm’s project and declined to disclose how much CIP was investing.

The spokesperson did confirm that CIP is “involved in a large-scale green hydrogen project in the Oaxaca region in Mexico.”

“Further development will take place in collaboration with local authorities and partners. We will provide further updates as the project progresses,” the spokesperson told Reuters.

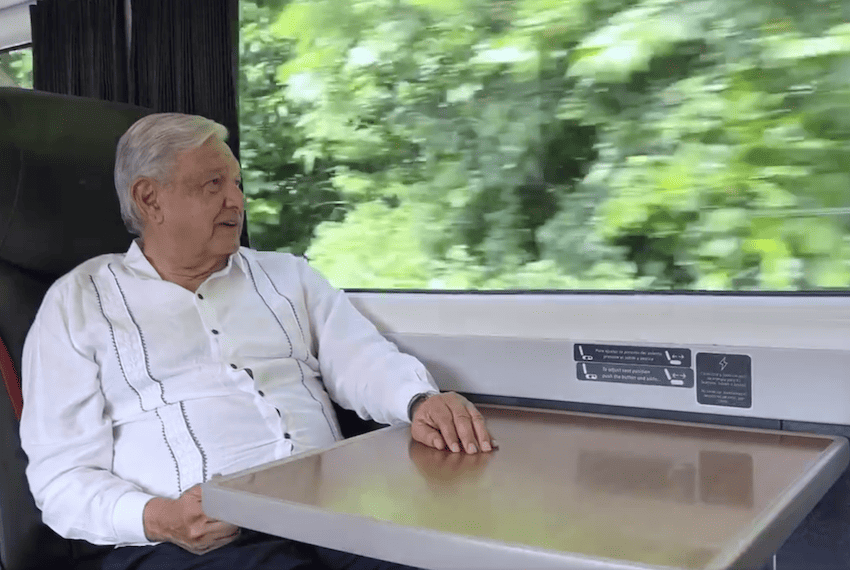

López Obrador, who held his Friday morning press conference in Oaxaca, also said that a passenger train will begin running between Salina Cruz and Coatzacoalcos on Dec. 22. He completed a test ride on the interoceanic service in September.

Once freight trains are running across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec – Mexico’s narrowest band of land between the Pacific and Gulf coasts – the government hopes to attract shipping companies that currently use the Panama Canal to move cargo between the eastern and western hemispheres.

Freight shipped from Asia, for example, could be unloaded in Salina Cruz and put on a train for a journey of approximately 300 kilometers to Coatzacoalcos. It could then be reloaded onto another ship before continuing on to the Gulf or Atlantic coasts of the United States.

Navy Minister José Rafael Ojeda Durán said in June that Mexico will become a “world shipping power” thanks to the construction of the interoceanic trade corridor.

He described the multi-billion-dollar trade corridor undertaking, which also includes the modernization of the Salina Cruz and Coatzacoalcos ports, as “one of the projects of the century” and asserted that it will stimulate economic development in the region and the entire country.

With reports from Reforma, El Universal and Reuters