There was a time when Mexico’s most iconic architects — Pedro Ramírez Vázquez, Ricardo Legorreta, and Ernesto Gómez Gallardo — were as known for their furniture designs as for their buildings. This overlap wasn’t accidental. The interplay between architectural spaces and the furniture within them creates an intimate connection that fosters thoughtful use of both.

Following in this tradition, architect José Miguel Márquez and Javier Gutiérrez, founded Mola Mx, a “creative workshop where we develop designer furniture that transcends time.”

Each piece from Mola Mx carries a distinctive personality, with many named after real people. “This great dream was born from the memories and experiences of architect José Miguel Márquez,” the company’s description reflects, underscoring the deeply personal nature of their creations.

When retro aesthetics meet minimalist Mexican design

By the late 1960s, optical art had surged in popularity, leaving an indelible mark on Mexican aesthetics. Nowhere was this more evident than in the bold graphics and signage of the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. Designed by Mexican architect Eduardo Terrazas and North American Lance Wyman, the visuals drew heavily from optical art and the intricate beadwork of the Wixárikas, an indigenous group renowned for their vibrant craftsmanship.

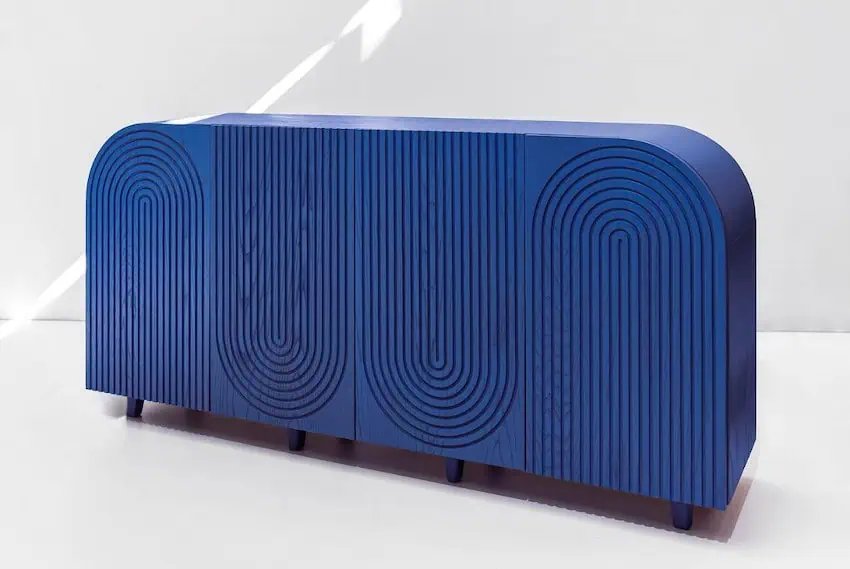

Today, Mola Mx channels this era, incorporating patterns of parallel and concentric lines reminiscent of that period. Yet, they offer a fresh, contemporary interpretation.

“It is the author’s design that transcends time,” the company asserts. Their creations blend rustic elements with minimalist elegance, often drawing comparisons to Japanese design for their simplicity and refinement.

Take the Marla credenza, inspired by the marimba, a traditional instrument from Chiapas. The María credenza, with its electric hues, celebrates Mexico’s lively spirit. Petra pays homage to the country’s use of palm, while the Isabel credenza captures the aesthetic essence of 1960s Mexico.

Paying tribute to Mexican heritage

Mola Mx extends its tribute to Mexican culture through special editions like the Raíces collection, inspired by talavera pottery, a craft recognized as Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO. Another standout is Encarnación, introduced at Design Week Mexico, which evokes the image of a revolutionary Mexican woman. “Encarnación aims to leave a lasting message,” the company says, inviting users to make the piece part of their personal narratives.

In a nod to inclusivity, designer Alex Sordia reimagined some of Mola Mx’s iconic models in a series inspired by the LGBTTTIQ+ movement, adding another layer of cultural resonance to their work.

Design as a personal statement

Mola Mx operates outside the confines of mass production. Each piece is crafted on demand, a process that can take two to three months, depending on the design. This bespoke approach ensures that every item undergoes a near-artisanal process.

Customization is another hallmark of their offerings. Clients can tailor their pieces by selecting wood types, finishes, and interior configurations, with additional fees for these bespoke options. “More than just static objects, we aim to convey a personality and a history that will be passed down from generation to generation,” the founders explain.

Mola Mx succeeds in this endeavor. Their designs, though timeless, feel ever-renewing, ready to be regarded as avant-garde in any era.

Ana Paula de la Torre is a Mexican journalist and collaborator for various outlets including Milenio, Animal Político, Vice, Newsweek en Español, Televisa and Mexico News Daily.