Six United States senators sent a letter to top Biden administration officials this week to raise concerns about the sale in the U.S. of Mexican avocados grown on illegally deforested land.

“We write regarding reports of widespread illegal deforestation and unsustainable water use linked to avocados imported from Mexico,” the six Democratic Party senators said in the Feb. 7 letter to U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack and Trade Representative Katherine Tai.

The senators, among whom are Tim Kaine of Virginia and Ben Cardin of Maryland, sought “additional information” regarding the Biden administration’s “efforts to address environmental degradation linked to these imports.”

They also requested that the U.S. government work with Mexico “to prevent the sale of avocados grown on illegally deforested lands to American consumers.”

The senators cited an article published in The New York Times in November (“Americans Love Avocados. It’s Killing Mexico’s Forests.”), noting that it says that avocado production in Michoacán and Jalisco — the only Mexican states certified to export the fruit to the U.S. — “has had a catastrophic impact on the environment and local communities.”

“A report by Climate Rights International further outlines the devastating toll of the U.S.-Mexico avocado trade: government officials in Michoacán and Jalisco identify avocado production as ‘a central cause of deforestation and environmental destruction in their states,’ including water theft,” the senators continued.

“The report also outlines how Indigenous leaders and others seeking to defend their forests and water have been threatened, attacked and killed.”

To help meet international environmental commitments made by the U.S., the Biden administration, “in cooperation with our Mexican partners, should work to prevent Mexican avocados produced on illegally deforested land from reaching U.S. markets,” stressed Kaine, Cardin, Peter Welch, Chris Van Hollen, Martin Heinrich and Jeff Merkley.

The senators advocated denying export certification “to orchards installed on recently illegally deforested land — a change that senior Mexican officials have reportedly expressed interest in making.”

“Because most Mexican avocado orchards are not on recently deforested land, the [Biden] administration could implement policy changes without significantly reducing American consumers’ access to avocados or harming the livelihood of law-abiding avocado farmers,” they said.

Climate Rights International (CRI), a California-based advocacy organization, said in a statement that the U.S. government “should act” on the senators’ advice.

“The environmental destruction and abuse fueled by Mexican avocado exports to the United States require urgent attention by both countries,” said Brad Adams, CRI’s executive director.

“Denying export authorization to avocado orchards installed on recently deforested lands would dramatically reduce the economic incentive to clear the forests or attack the people defending them,” he said.

CRI said that the opposition of Michoacán and Jalisco residents, including Indigenous leaders, environmentalists, journalists, and academics, to the destruction of forests due to avocado production is “no match for the profits to be made selling avocados to corporations that export the fruit.”

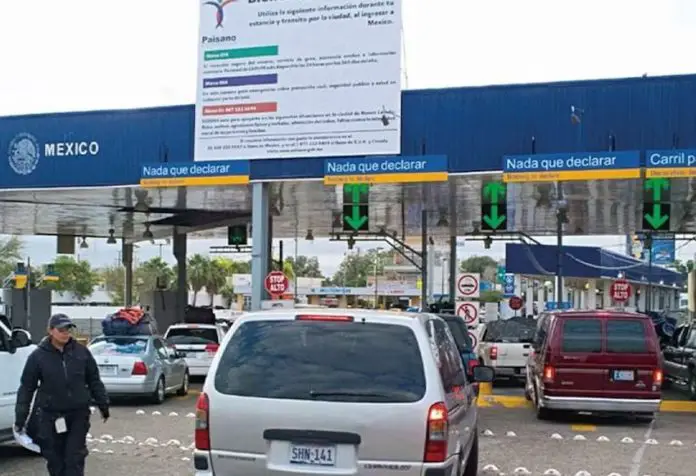

“Mexico supplies four out of five avocados eaten in the United States, in exports worth US$3 billion per year. The U.S. market — which has tripled in size since 2000 — is the main factor motivating avocado producers to destroy forests to establish orchards,” the organization said.

The senators’ airing of their concerns comes ahead of the Super Bowl this Sunday, a day on which avocado consumption in the U.S. reaches its annual peak, mainly due to the use of the so-called alligator pear to make guacamole.

The Michoacán Ministry of Agriculture said last week that Mexico would send 138,000 tonnes of avocado to the United States to meet Super Bowl demand.

Mexico — the world’s largest avocado producer — is easily the top exporter of avocados to the United States. In 2023, a record high of 1.14 million tonnes of Mexican avocados were shipped north of the border, according to agriculture consultancy Grupo Consultor de Mercados Agrícolas.

Mexico News Daily