A poster came my way announcing an all-day excursion called “La Ruta del Colibrí” — the Hummingbird Route. It promised a three-part adventure quite unlike any other, so I signed up and I must say the organizers kept their promise.

This activity was conceived by people in the little town of Ahualulco de Mercado, Jalisco, located 60 kilometers west of Guadalajara. Ahualulco natives have always known that curious and wonderful attractions surround their town and, at last, have decided to share some of them with the rest of the world.

We met in the town square at 7:00 a.m. I found that 16 people had signed up for La Ruta del Colibrí and had obviously gotten out of bed very early that morning.

Birdwatching at 7 a.m.

The early start was de rigueur because the first item on the schedule is bird watching and the best time to see birds is right after sunrise.

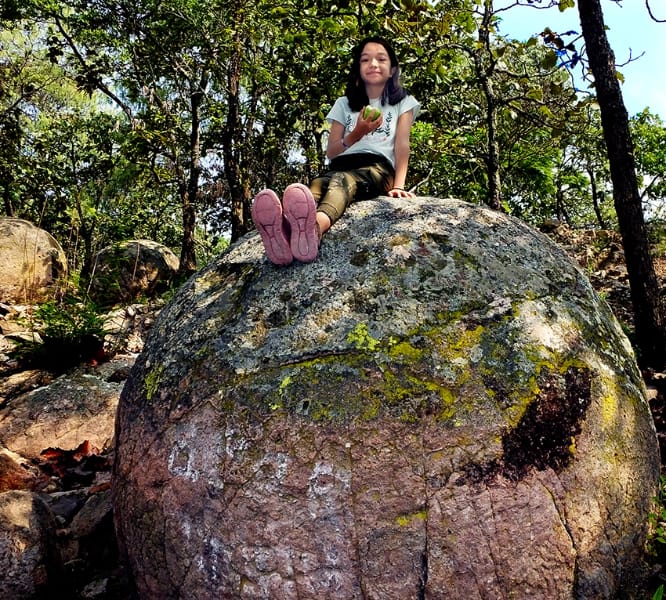

Off we went in a van along a picturesque dirt road that winds its way through a magnificent forest up to one of the most extraordinary geological sites in the world: the Cerro de Piedras Bola. This mountaintop in the Sierra del Águila is covered in gigantic, remarkably spherical stone balls.

We parked a kilometer and a half from the top and proceeded on foot. Leading the group was biologist and self-made ornithologist Julio Álvarez, who passed out binoculars to all.

As we made our way up the road, we were introduced to all kinds of birds, ranging from the astonishingly beautiful red-faced warbler, as well as the plainest bird imaginable: the brown-backed solitaire. Known as the clarín jilguero in Spanish, this dull-looking bird, surprises with its glorious song, which sounds like three flutes being played simultaneously. Yes, we saw plenty of beautiful hummingbirds as well.

70 giant stone balls

At the top, we snacked among the huge balls of volcanic rock – which measure measuring close to nine meters in circumference – as we listened to the latest theories of how the Piedras Bola were formed were formed, from Canadian geologist Chris Lloyd, who accompanied us on the walk.

Researchers have counted more than 70 giant balls on this hilltop and as far back as 1967 a writer for National Geographic Magazine spent time here trying to figure out just where they all came from.

Hot and sweaty after our hike, we jumped back in the van and proceeded down the mountain to the Hummingbird Temazcal, hidden away in a jungly spot nearby.

Inside a traditional Mexican temazcal (sweat lodge)

Our hosts, Maru Magaña and Marco Martínez, explained that the word temazcal means “house of the hot rocks” and is part of one of the oldest traditions in the world.

Temazcals and sweat lodges were used, perhaps monthly by just about every community up and down the continent of America and in many other parts of the world. Fortunately, some places all over Mexico still follow the temazcal rituals, allowing you to participate in one of the most important and ancient traditions of the human race.

So, wearing shorts or long white dresses, we were called to the sweat lodge by the blowing of a conch shell. Next, we were purified by incense, and then, after making an offering of tobacco, we found ourselves sitting together in darkness as hot volcanic rocks –traditionally called abuelitas (grandmas) were brought in one by one and placed in a hole in the center of the temazcal.

“¡Bienvenida, Abuelita!” we would greet each of them.

As none of us was a tough guerrero (warrior), our group remained inside the temazcal for only four puertas (doors), each of which is a period of time spent in darkness, the entrance having been covered with a blanket after seven new abuelitas are brought in.

Once the door is closed, the hot rocks and all the participants are sprinkled with aromatic plants dipped in water. Clouds of steam fill the temazcal.

Inside the little hut, there are also a drum and castanets.

Someone begins to sing an ancient song with easy lyrics, which we soon repeat. The hypnotic drum beat echoes In the misty darkness, doing its magic. In no time at all, we are transformed into a community of friends.

Twenty-eight hot rocks later, we and the bandanas on our heads are completely soaked by sweat and much sprinkling.

The temazcal is like a womb. Slowly, we crawl out of it, one by one, each of us touching his or her head to the floor in reverence. We are reborn.

Washing off the sweat is a delightful experience and the fresh watermelon and orange slices awaiting us outside taste extraordinarily delicious. But this is just a snack. We are ravenously hungry and lose no time getting back into the van. We are heading for El Restaurante de la Tía Lancho, located in the pueblo of Teuchiteco, a two-kilometer drive from the temazcal.

The pre-Columbian restaurant of Tía Lancho

Tía Lancho is a member of Las Mujeres de Maíz, founded in 2011 by Mexican cookbook guru Maru Toledo. Members of the group are graduates of Toledo’s “Smoky School of Gastronomy.” They are skilled not just in cooking without the benefit of gas or electricity but also in finding or growing all the herbs and plants needed for making a meal.

Whether Tía Lancho serves you mole, pipián, espinazo, or hand-made tortillas, it will taste far more delicious than what you might find in a regular restaurant, and apart from enjoying your meal, you may also be fascinated by a visit to the old-style smoky kitchen where it was made.

Here, you might even try using a molcajete or a metate and discover just how strong pre-Hispanic cooks had to be.

If you want to visit any of these sites or join in on the next Ruta del Colibrí, just contact the Kan Baálam Travel Agency in Ahualulco. “We can pick people up at the Guadalajara airport,” says owner Alejandro López, “and, yes, we speak English.”

Participants in the Hummingbird Route say they were amazed at how much they learned about temazcals and traditional Mexican food…not to mention those amazing Giant Stone Balls!

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.